The Book of Revelation sits at the farthest edge of the biblical canon like a storm cloud ablaze with fire, its thunder rolling through centuries of human imagination, its lightning cracking across the night sky of history.

It is not a gentle text. It does not whisper soft lullabies about peace and order; it roars with images of beasts, bowls of wrath, burning stars, and blood upon the moon. It is at once terrifying and transcendent, cryptic and cosmic, maddening and magnificent. Revelation has been read as prophecy, poetry, apocalypse, allegory, political critique, theological thunderclap, and eschatological epilogue.

It is a book that dares the reader to see beyond surface reality, to peer into the veil of history’s hidden theater where God and empire, Christ and chaos, eternity and annihilation wrestle in visions of staggering symbolic density.

To examine Revelation is to enter a labyrinth where language is not literal but layered, where numbers become metaphors, where beasts become empires, where the sea itself seems to carry secrets in its abyss.

Scholars and saints, mystics and madmen alike, have wrestled with this text, seeking to decode its strange visions. Some have wielded it as a roadmap of the future, others as a mirror of the present, still others as a mythic drama of timeless spiritual struggle. The Book of Revelation has been both weapon and wonder, both warning and witness, shaping not only Christian eschatology but Western imagination itself. Without it, Dante would lack his infernal architecture, Blake his visionary fire, T.S. Eliot his hollow men, and modern cinema half its dystopian aesthetics.

At its core, Revelation calls itself ἀποκάλυψις Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ—“the unveiling of Jesus Christ” (Revelation 1:1). Apocalypse does not mean destruction, as pop culture insists; it means unveiling, disclosure, revelation. What is unveiled is not only the fate of empires or the chronology of the cosmos, but the radical sovereignty of God, the supremacy of Christ, and the paradoxical triumph of the slain Lamb over the dragon of darkness. It is both historical letter and cosmic liturgy, political critique and prophetic imagination.

The Author and Audience

Tradition attributes Revelation to John, exiled on the island of Patmos “because of the word of God and the testimony of Jesus” (Rev. 1:9). Whether this John is the beloved disciple, the evangelist, or another prophetic figure is debated. The text is steeped in Old Testament imagery, referencing Daniel, Ezekiel, Isaiah, and the Psalms, suggesting its author was a Jewish Christian saturated in Scripture. Its first audience were seven churches in Asia Minor—Ephesus, Smyrna, Pergamum, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia, and Laodicea—each receiving letters that combine rebuke, encouragement, and apocalyptic warning. Written during a time of persecution (likely under Emperor Domitian, ca. 95 AD), Revelation was a coded critique of Rome’s imperial cult and a call for Christians to endure faithfully, resisting assimilation into the beastly machinery of empire.

Elaine Pagels, in Revelations: Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in the Book of Revelation (2012), argues that John’s visions were not detached from history but were deeply political, envisioning Rome as Babylon, the beast drunk on the blood of the saints. Others, such as Craig Keener in Revelation (NIVAC, 2000), emphasize the pastoral and theological function: it was written to fortify the faithful against compromise. Both readings converge in seeing Revelation not as fantasy but as fierce resistance literature, a text that baptized imagination to perceive empire’s brutality as beastly rather than divine.

The Structure of the Storm

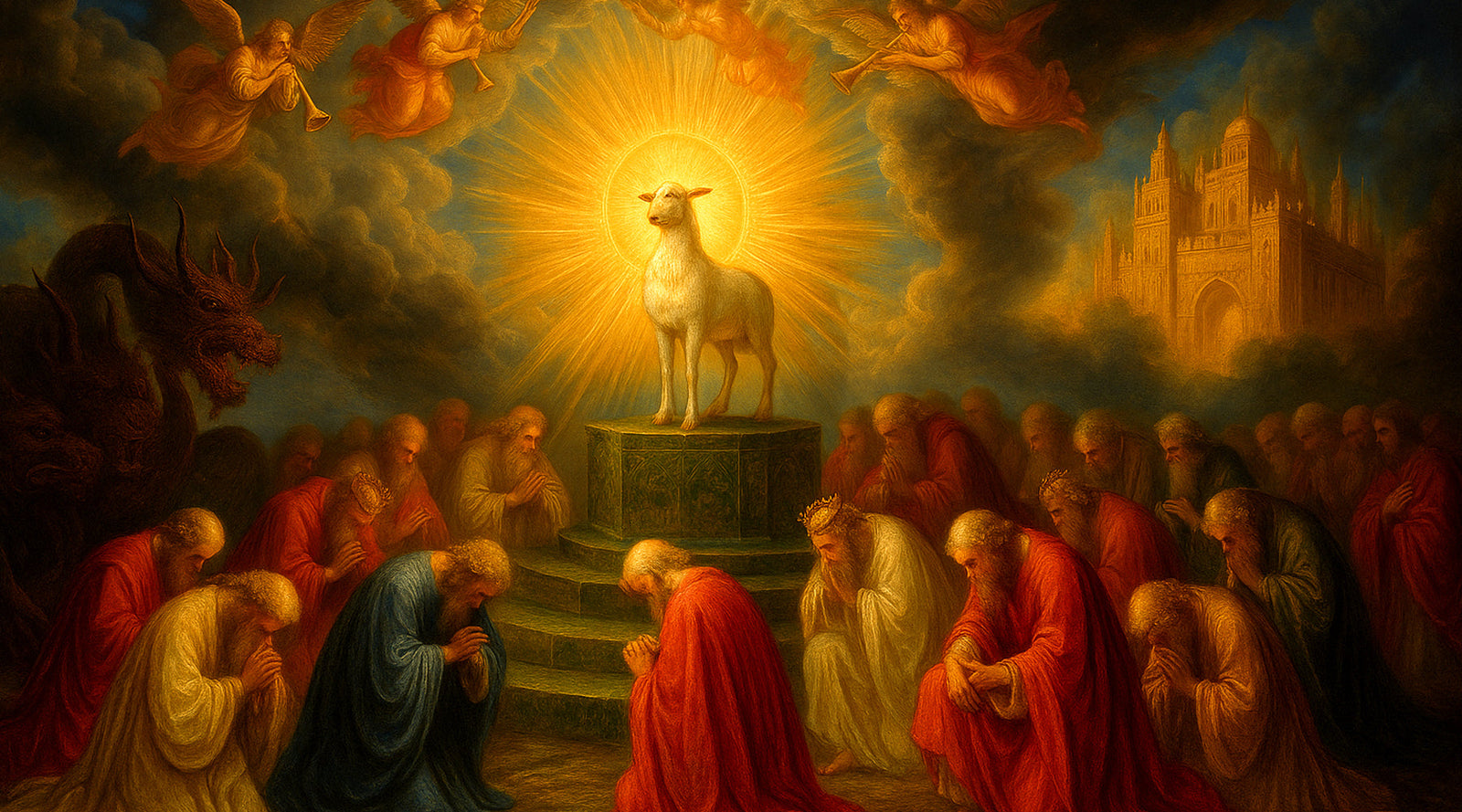

To summarize Revelation is to attempt to chart a hurricane. The book opens with John’s vision of Christ in dazzling, terrifying glory (Rev. 1). This is followed by the seven letters to the churches (Rev. 2–3), then by the throne-room vision where heaven resounds with worship of the Creator and the Lamb (Rev. 4–5). What follows is a cascading sequence of sevens—seven seals, seven trumpets, seven bowls—each unleashing symbolic judgments upon earth. Interwoven are visions of beasts, Babylon, the dragon, the two witnesses, the mark, the millennium, the final battle, and finally the descent of the New Jerusalem.

The number seven—biblically the number of completeness—shapes the entire book. Yet the progression is not linear but cyclical, like spirals of thunder echoing back upon themselves. Richard Bauckham, in The Theology of the Book of Revelation (1993), argues that Revelation does not present a chronological roadmap of future events but a series of visions, intensifying perspectives on the same cosmic reality: God’s sovereignty over history and the ultimate victory of Christ.

Decoding the Symbols

The beast with seven heads (Rev. 13) has been read as Rome, its seven hills mirrored in the seven heads, its blasphemous power demanding worship. The mark of the beast—666—is often identified with Nero Caesar, whose name in Hebrew gematria sums to that number. Babylon the Great, clothed in scarlet and gold, drunk with the blood of the saints (Rev. 17), evokes Rome as the harlot empire. Yet these symbols transcend history; they apply to every empire that wields idolatrous power, every system that demands allegiance over against God.

The dragon (Rev. 12) is Satan, the ancient serpent of Eden, who wages war against the woman clothed with the sun (a symbol often read as Israel, the Church, or Mary). The Lamb (Rev. 5)—slain yet standing—is Christ, paradoxical power in weakness, the center of the vision. Revelation unveils not simply beasts and battles, but the deeper truth that the way of the Lamb, not the way of the sword, is the true victory. This is its radical inversion: conquest comes not through violence but through the cross.

The Eschatological End

At the climax, the Rider on the White Horse appears, “Faithful and True,” whose robe is dipped in blood and whose name is “The Word of God” (Rev. 19:11–13). Armageddon is invoked, not as a Hollywood battlefield but as a cosmic confrontation of good and evil. The dragon, beast, and false prophet are cast into the lake of fire. The dead are judged before the Great White Throne. Then comes the vision of a new heaven and a new earth, the holy city, New Jerusalem, descending like a bride. No more tears, no more death, no more curse. The story that began in Eden ends in a renewed creation, with God dwelling among humanity (Rev. 21–22).

Interpretive Approaches

Scholars distinguish four main interpretive lenses:

-

Preterist – Revelation refers primarily to first-century events (persecution under Rome, destruction of Jerusalem).

-

Historicist – Revelation maps the course of church history from John’s day to the present.

-

Futurist – Revelation predicts literal end-time events yet to come.

-

Idealist (or Symbolic) – Revelation is timeless allegory, depicting the ongoing struggle between good and evil.

Each school has insights and pitfalls. The futurist reading dominates modern evangelical imagination, fueling Left Behind novels and end-times charts. The preterist grounds the text in its historical context. The idealist preserves its timeless symbolism. The historicist once dominated Protestant polemics against the papacy. Many scholars, such as G.K. Beale (The Book of Revelation, 1999), argue for a mixed approach, seeing Revelation as both historically rooted and eschatologically expansive.

The Grit and Glory

Revelation is not polite literature. It traffics in grotesque imagery: rivers of blood, plagues, locusts with human faces, a whore astride a scarlet beast. It is a text that shocks, disorients, destabilizes. But it does so with purpose. John’s world was dominated by the propaganda of empire, Rome projecting itself as eternal, divine, beneficent. Revelation unmasks the empire as beast and Babylon, its beauty a veneer for violence. It tells the persecuted church: Rome is not ultimate, Christ is. Empire burns, but the Lamb reigns. As Eugene Peterson once wrote, “Revelation does not tell us what will happen, it shows us what is happening.”

The poetic fire of Revelation is its refusal to be domesticated. It reads like literature carved into lightning, like prophecy painted in blood and thunder. Its long sentences coil with alliteration and metaphor, its images blaze with surreal intensity, its cadence rises and falls like waves of war drums. It is visionary literature in the truest sense: not mere prediction but perception sharpened to apocalyptic sight.

Revelation and Modernity

The relevance of Revelation today is not limited to debates over rapture timelines or end-times charts. Its vision speaks whenever empire rises, whenever idolatry is enthroned, whenever the weak are crushed under the heel of the powerful. Babylon is not only Rome but every system that commodifies, consumes, and corrupts. The beast is not only Nero but every totalitarian impulse. Revelation tells us to see the world as it really is: the pomp of power is but a mask for monstrosity; the Lamb reigns through sacrifice; the final word belongs not to empire but to God.

Scholars like Adela Yarbro Collins (Crisis and Catharsis, 1984) emphasize the psychological function: Revelation provided catharsis for oppressed Christians, transfiguring suffering into cosmic significance. Modern readers, facing ecological collapse, political chaos, or cultural despair, may find in Revelation a similar catharsis. It tells us history is not a closed loop of despair but a drama moving toward renewal.

The Summation

To summarize Revelation is impossible without reduction. It is thunder, not thesis. Yet we may say this: Revelation unveils Christ as the cosmic conqueror who conquers by the cross, exposes empire as beastly idolatry, and promises a new creation where God dwells with humanity. It is both warning and witness, demanding that readers “come out of Babylon” (Rev. 18:4) and remain faithful unto death. It is not a puzzle to be solved but a vision to be entered, a poem to be prayed, a fire to be felt.

The Book of Revelation is not a codebook for conspiracy theorists or a canvas for Hollywood apocalypse; it is the church’s wildest hymn of hope, its fiercest act of resistance, its most surreal symphony of sovereignty. It ends not in despair but in dazzling doxology: “The Spirit and the bride say, ‘Come’” (Rev. 22:17). The curtain falls not with annihilation but with invitation.

And so Revelation remains—maddening, majestic, magnificent—calling us to see beyond the beasts of the moment to the Lamb who was slain, who is, and who is to come. To read it is to stand in the storm of symbols and still hear the whisper of hope: Behold, He makes all things new.

Sources Referenced:

- The Holy Bible, Book of Revelation (NRSV, ESV, NIV translations consulted).

- Bauckham, Richard. The Theology of the Book of Revelation. Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Beale, G.K. The Book of Revelation. Eerdmans, 1999.

- Pagels, Elaine. Revelations: Visions, Prophecy, and Politics in the Book of Revelation. Viking, 2012.

- Keener, Craig. Revelation (NIV Application Commentary). Zondervan, 2000.

- Collins, Adela Yarbro. Crisis and Catharsis: The Power of the Apocalypse. Westminster, 1984.

- Peterson, Eugene H. Reversed Thunder: The Revelation of John and the Praying Imagination. HarperOne, 1988.

When John saw beasts and Babylon, he also saw the Lamb—radiant, unshaken, victorious. Revelation isn’t just prophecy; it’s a reminder to live bold, unashamed, and set apart in a world that bows too easily to lesser kings. That’s the heartbeat behind Faith Mode Streetwear. Every stitch, every thread, every design is a declaration that faith isn’t fragile—it’s fire. Step out of Babylon. Stand with the Lamb. Wear what you believe.